“Okay, so honestly, why are you doing this? Did something bad happen to you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, usually that’s why people do things like this, they are running away.”

“Why do you go camping, Stan? Did something bad happen to you?”

“No.”

“Exactly.”

“But like, you don’t even come from a place that would prepare you for this. You don’t know what you’re letting yourself in for.”

“I thought you said you came from Florida?”

“You know bears in Denali maul twenty people to death every year, right?”

Then I smiled at him and passed him my Collected Words of Jack London with all of the feminist and socialist stories and passages earmarked and annotated for his consideration. I know he is lying about the bear statistic because I already looked it up.

What happened to me? Nothing. I think that that is the point. I need to experience something visceral to placate the hunger. And I am sick of the men that want to keep it from me. Maybe you could say patriarchy happened to me. So like a dog cast out into the rain maybe I do leave, to go cry myself a big fat fucking two-hearted river. To sleep in an open field! To travel west! To walk freely at night!

—The Word for Woman is Wilderness, Abi Andrews

I tried to read On the Road by Kerouac on my way to the Himalayas. It was 2013 and Wild by Cheryl Strayed had been published the year prior. Sitting in Heathrow during a five-hour layover, I was itching to read something that’d ignite the traveler within me, something exciting yet mundane, profound yet accessible.

I’d developed an interest for adventure nonfiction in high school, starting with classics like Into the Wild and Into Thin Air, and moving on to lesser-known gems like A Man’s Life and Buried in the Sky. Wild was the first adventure book I’d ever read about a woman. I was nineteen years old when it came out. Nineteen years old.

(I never finished On the Road.)

At a Buffalo Wild Wings in Ohio, I got into an argument about the movie Black Panther.

My point: Black Panther is important because its protagonist is a black superhero, and kids need to see that, especially black kids. His point: Empathy allows us to identify with people we don’t look like; why the fuss? The Cavs playoff game blared on TVs all around us, and I remember swelling with indignation and frustration, trying to explain why diverse representation mattered. He could see the storms in my eyes. Honestly, this isn’t an issue I’ve thought about much, he told me. I deflated a bit then. Of course he hadn’t. He sees himself everywhere. The world was built to mirror back his experiences, his identity; he doesn’t have to try.

It seems silly to state this but also strangely necessary: People experience things differently. We are not all treated similarly when we travel. We do not all feel identically when alone in the woods with only ponderosas for company. We are not the same.

On a cold morning outside of Lake Tahoe, I woke up to frost inside my car. It was only October, but already the Golden State was getting ready for ski season, packing away its swimsuits and water goggles, dusting its trails with early morning snow. I set up my small stove and boiled water for instant coffee and oatmeal, waiting for the sun to slip above the pines. A woman and her husband were walking among the sparse campsites, and they stopped about twenty yards away when they noticed me. I don’t remember much about our conversation, but I do remember their body language like a stop-motion reel. Her first. Then him. Slowly. Only after it was deemed safe. After I was deemed safe, not a frightened animal prone to biting. The only words I remember are not even words but a sentiment: Are you okay? I explained that living out of your car was kind of a fad for young people these days, and that this was a chosen adventure, not a desperate flight. It felt strange having to explain my choices.

I’m not sure men ever have to do that.

A Tumblr post I once read said that when women scream people wonder what is wrong, but when men scream people wonder what they’re going to do. I think about that a lot. How much of our lives are encoded by violence. Gendered violence, really. One time a male friend told me about a situation at a truck stop where a man cornered him in the bathroom; he had to whip out his pocketknife in order to escape before things really went awry. He was drunk and crying when he told me this story. I felt bad. But I also wasn’t surprised. This is the world we live in. This is the price we pay for existence. But he’s never had to pay this price before because he’s a man and men often get passes for things like this. You are not alone, my friend. Welcome to the sisterhood.

Did you know that the female record-setter for the most summits on Everest works as a dishwasher in Hartford, Connecticut, at a Whole Foods? How does that make you feel? If you look at the Wikipedia article “List of Mount Everest summiters by number of times to the summit” each female mountaineer is denoted by the female gender symbol next to their name. There is no symbol next to the male names. How does that make you feel?

I read more female adventure books after Wild. There was Girl in the Woods by Aspen Matis where she hikes the PCT after experiencing sexual trauma. There was Where the Mountain Casts Its Shadow by Maria Coffey–one of my all-time favorite adventure books–that grapples with being a loved one to thrill-seekers and how they are always leaving you, sometimes forever, and what it means to be in love with loss. They were good books, even great books. But they were somehow still about men. Men were the cause, the impetus for emotions, sometimes the entire journey. Can’t women exist alone? Can’t the wilderness belong to them too, without fear, without hesitation? Can’t we have a book that extols travel and nature with the same literary backbone as fucking Kerouac?

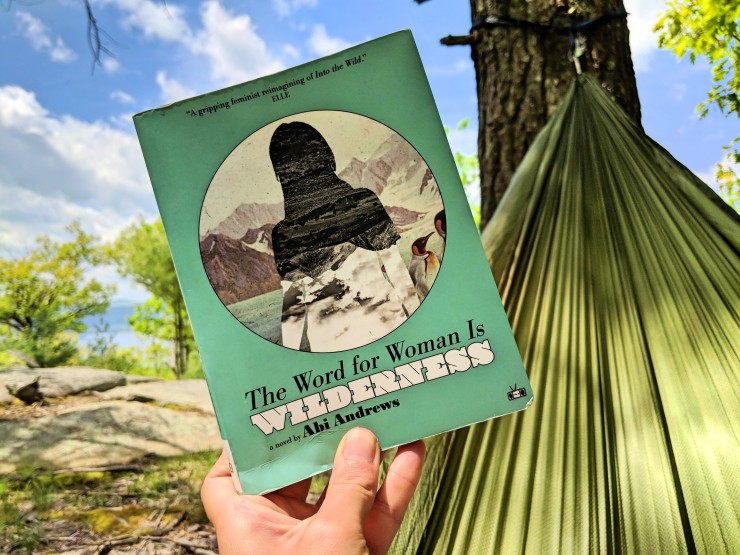

Then I found The Word for Woman is Wilderness by Abi Andrews. It is everything I wanted. It is fiction but it feels like nonfiction. It has the journal-like quality I was hunting for.

Sometimes women go into the wild simply because they want to go. Not because they are running away but because they are running toward. And women have their own adventures in the wild. Their own stories. We need to listen better. We need to seek out their unadulterated voices more.

If you’re reading my blog, you should consider reading The Word for Woman is Wilderness. It is not an easy read. It is not brimming with action. It references cosmological physics far more than you would expect a nature book to. But because it is difficult and genuine and informative is why you should read it. Because if you list every adventure book you’ve read about a man, and every one you’ve read about a woman, and every one you’ve read about a person of color, you may come to the conclusion that you should read a little broader.

So you should read this book.

(And purchase it because buying this book supports an independent publisher and lets them know that the public values books like this. And we do. We do.)

(ALSO, if you have any adventure book recommendations about/by authors of color, I’d love to hear them.)

Have you read “Grandma Gatewood’s Walk”? She was first woman to solo the Appalachian Trail and did it in multiple pairs of tennis shoes! She did it three times in fact, if I remember right. Of course, I could comment on the title and say it probably wouldn’t Have been Grandpa Whoever.

Change my email see below

LikeLiked by 1 person